Issue 112

Term 1 2020

Improving reading outcomes for students with dyslexia

Anna Boyle answers the question: what is dyslexia? and explores how specially designed Dyslexic Books can improve reading outcomes for students.

What is dyslexia?

Dyslexia is a specific learning disorder that involves difficulty in learning to read or in interpreting letters and words. According to the Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5, American Psychiatric Association 2013), it is a developmental disorder that begins by school age, although it may not be recognised until later. The prevalence of dyslexia depends upon the precise definition of the disorder and the criteria used for its diagnosis (Snowling 2013), with dyslexia associations around the world (eg Australian Dyslexia Association 2018) estimating that it affects between 10 and 20 per cent of the population. Dyslexia does not affect intelligence. Research has demonstrated that while in typical readers intelligence and reading are dynamically linked, readers with dyslexia can have high intelligence, yet read at a comparatively much lower level (Shaywitz & Shaywitz 2014).

Unlike speech, which is an ‘innate’ ability acquired by humans, reading is a complex task that requires specific instruction. It involves the activation of several auditory and visual processes in the brain at the same time. In an alphabetic language such as English, text characters represent phonemes, the basic units of spoken sound. Phonemes make up syllables, which in turn make up words. Words are grouped into phrases and sentences that contain meaning.

The first step in learning to read an alphabetic language is phonological, and involves decoding text characters into phonemes (Adams 1990). The ability to discern the sounds, and the sequence of sounds, in a word, is called ‘phonemic awareness’. Readers rely on this phonemic awareness and letter-sound knowledge to decode words.

Once this decoding is accomplished, the reader internally ‘hears’ each word. This activates the speech–understanding parts of the brain to obtain the meaning of the words and thereby understand the sentences that comprise them. As readers become more proficient, they start to recognise whole words, and even phrases, by shape. For example, proficient readers can very quickly read and understand a phrase such as ‘How are you?’ simply by looking at it and recognising the words. This is a function known as ‘sight word recognition’ that involves the visual processing parts of the brain and enables reading fluency.

Many students with dyslexia have a specific difficulty in automatising word recognition (Vellutino et al 2004). This is likely based on phonological skill deficiencies associated with phonological coding deficits. Research and experience have shown that while there is no cure for dyslexia (since it is neurobiological), it can be remediated with appropriate interventions. These include direct, explicit and multi-sensory programs that include the five essential skills for reading: phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary and comprehension (Hempenstall 2016).

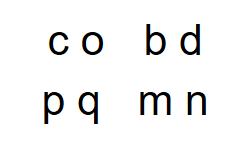

Figure 1. Many letters in the English alphabet are mirror images of each other or have similar characteristics.

Students with dyslexia also demonstrate deficits in rapid automatised naming (RAN). Many of the tests involved in diagnosing dyslexia include RAN tasks that measure how quickly a student can name letters (eg the Test of Word Reading Efficiency, or TOWRE).

A particular problem with the English alphabet is that many letters have similar characteristics, and some are mirror images of each other (see Figure 1). This makes letters difficult to distinguish, and readers with dyslexia often report rotating, flipping and/or reversing letters. These similarities may also contribute to the RAN deficiency mentioned above.

How changing the format can improve reading outcomes

There is a growing body of research investigating how changing the format of a text can improve reading outcomes for students with dyslexia. Zorzi et al. (2012) showed that a simple manipulation of letter spacing substantially improved text reading performance of participants, without any prior training. Their results showed that participants read 20 per cent faster on average and made 50 per cent fewer mistakes. They concluded that the extra-large letter spacing improved reading outcomes because students with dyslexia are abnormally affected by ‘crowding’, a visual processing deficit that affects letter recognition.

Schneps et al. (2013) used eye-tracking to investigate the effect of shorter lines for people with dyslexia. They also looked at other factors, including replicating the results of Zorzi et al. with letter spacing. Schneps et al. found that participants’ reading speeds improved by 27 per cent, and the number of eye fixations was reduced by 11 per cent. An eye fixation is simply the point at which the eyes comes to rest on the page in the process of reading.

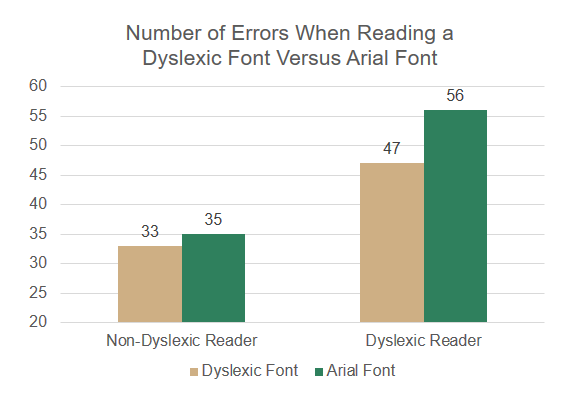

Pijpker (2013) examined whether the reading performance of participants with dyslexia could be improved by changing the font and background colour of the text. His research included two groups (participants with dyslexia and participants who did not have dyslexia) and compared results when reading in Arial font compared to a dyslexic font (see Figure 2). The results showed that there was a significant main effect for the participants with dyslexia when reading in the dyslexic font. On average, reading in the dyslexic font reduced the number of errors by 16.1 per cent for people with dyslexia. Changing the font for participants who did not have dyslexia did not seem to have a significant effect (a decrease in errors of 5.7 per cent).

Figure 2. The number of errors when reading Arial font compared to a dyslexic font. Adapted from (Pijpker 2013).

What are Dyslexic Books?

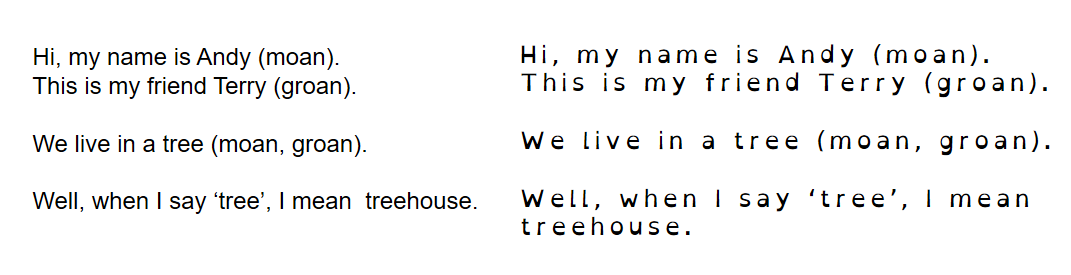

Dyslexic Books are specially designed books for readers with dyslexia. Drawing from the research discussed above, the books are formatted to optimise reading outcomes. This includes printing in a larger font size, increasing the spacing between letters, words and lines, and using a specially designed dyslexic font, Open Dyslexic (see Figure 3).

As discussed above, many letters in English have similar characteristics or are mirror images of each other. The Open Dyslexic font alleviates some of the difficulties typically reported by readers with dyslexia, such as swapping or flipping letters and skipping lines without noticing. It does this by differentiating each letter, using distinctive features and changing letters so that they are no longer mirror images of other letters. Some of the features include:

- bolded capitals

- bolded bottoms of letters

- slanted letters

- larger letter openings

- increased spacing between letters.

Dyslexic Books works with librarians (in both school and public libraries) to encourage a greater selection of writing to be made available in accessible formats in their library collections.

Dyslexic Books (through its parent company Read How You Want) has relationships with many of the major publishers in Australia and around the world. This enables a wide selection of titles to be made available in the dyslexic format, usually within a month of publication. Dyslexic Books works with librarians (in both school and public libraries) to encourage a greater selection of writing to be made available in accessible formats in their library collections. As such, discounts are available to schools and libraries when ordering books through the Dyslexic Books website dyslexicbooks.com.

Image credits

Cover image supplied by SCIS. All other images supplied by Anna Boyle.

References

- Adams, M. J. (1990). Beginning to read: Thinking and learning about print. Cambridge, MA: Bolt, Beranek, and Newman, Inc.

- American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Retrieved from https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/dsm/dsm-5

- Australian Dyslexia Association (2018). What is Dyslexia? Retrieved 9 August 2019 from https://dyslexiaassociation.org.au/dyslexia-in-australia/

- Hempenstall, K. (2016). Read about it: Scientific evidence for effective teaching of reading. Retrieved 9 August 2019 from The Centre for Independent Studies https://www.cis.org.au/app/uploads/2016/07/rr11.pdf

- Pijpker, T. (2013). Reading performance of dyslexics with a special font and a colored background. University of Twente, The Netherlands. Retrieved 4 June 2018 from http://essay.utwente.nl/63321/1/Pijpker,_C._-_s1112430_%28verslag%29.pdf

- Schneps, M. H., Thomson, J. M., Sonnert, G., Pomplun, M., Chen, C., & Heffner-Wong, A. (2013). Shorter lines facilitate reading in those who struggle. PloS one, 8, e71161. doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0071161

- Shaywitz, S., & Shaywitz, B. (2014). For all those who care deeply about dyslexia: A major step forward. The Yale Centre for Dyslexia and Creativity. Retrieved 14 October 2014 from http://dyslexia.yale.edu/ABOUT_Shaywitz_MajorStepForward.html

- Snowling, M.J. (2013). Early identification and interventions for dyslexia: A contemporary view. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 13, 7-14. doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-3802.2012.01262.x

- Vellutino, F.R., Fletcher, J.M., Snowling, M.J., & Scanlon, D.M. (2004). Specific reading disability (dyslexia): What have we learned in the past four decades? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 45, 2-40. doi.org/10.1046/j.0021-9630.2003.00305.x

- Zorzi, M., Barbiero, C., Facoetti, A., Lonciari, I., Carrozzi, M., Montico, M., & Ziegler, J.C. (2012). Extra-large letter spacing improves reading in dyslexia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109, 11455-11459. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1205566109.f