Issue 111

Term 4 2019

Digital fluency vs. digital literacy

Clint Lalonde, educational technologist and advocate for open education practices in higher education, explores the critical differences between digital fluency and digital literacy.

Recently I’ve been doing a bit of research on digital literacy/digital fluency, to find out whether our post-secondary institutions are currently offering any programs and initiatives that will help instructors to use digital tools effectively.

Many organisations have identified a lack of digital literacy among post-secondary educators as a barrier to the adoption of educational technology. In 2014, the NMC Horizon Report noted this:

Faculty training still does not acknowledge the fact that digital media literacy continues its rise in importance as a key skill in every discipline and profession. Despite the widespread agreement on the importance of digital media literacy, training in the supporting skills and techniques is rare in teacher education and non-existent in the preparation of faculty.

This view was reiterated in the 2018 Horizon Report, showing that the issue of digital literacy is an ongoing and significant issue in educator training. Reports from both JISC (2018) and Educause (2017) also highlight a lack of digital literacy as a significant issue for higher education. The JISC report in particular, highlights the damage to student learning that can be done when faculty members lack digital competency:

The report also shines a light on the digital competencies of staff, with many students reporting frustration when lecturers struggle to use digital systems correctly, saying it wastes time and restricts access to digital resources.

To help address this gap, organisations have begun devoting resources to increasing the digital literacy of faculty and instructors. Initiatives such as eCampus Ontario’s Extend program, the University of Brighton Digital Literacies Framework, and the Irish Education Digital Skills in Higher Education initiative are examples of initiatives aimed at increasing the digital fluency of faculty and staff in higher education.

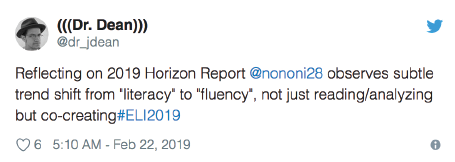

A tweet from Jeremy Dean confirmed what I have been seeing in my research. There is a subtle but important shift in the way we are talking about digital literacy.

This is a good shift in language, as being digitally literate and being digitally fluent are different things. Digital fluency is a much more holistic term than digital literacy. While many definitions of digital literacy focus on the development of basic digital skills and competencies, digital fluency goes further. It focuses on the metacognitive skills required to transfer those digital skills from one technology to another, and to make sound, nuanced decisions about technology use.

I see the difference between literacy and fluency as a continuum. Literacy is a pause on the way to fluency, although an important one, because you cannot become fluent until you become literate. But literacy shouldn’t be the end-game for those of us who support technology-enabled teaching and learning practice. We should be shooting for fluency.

Here is Jennifer Sparrow, Senior Director of Teaching and Learning at Penn State University, on the difference between digital literacy and digital fluency:

How is digital fluency different from digital literacy? In learning a foreign language, a literate person can read, speak, and listen for understanding in the new language. A fluent person can create something in the language: a story, a poem, a play, or a conversation. Similarly, digital literacy is an understanding of how to use the tools; digital fluency is the ability to create something new with those tools.

Using this example, I consider that author Anthony Burgess reached the highest level of fluency. He twisted and modified English (and Russian) to create a subculture dialect (called Nadsat) for his novel A clockwork orange. Such evolved fluency helps me to see the differences between literacy and fluency.

There are other ways to be digitally fluent, such as being able to move nimbly and confidently from one technology to another. A digitally literate instructor may be able to set up and configure tools within the confines of their learning management system, and even understand when to use those tools to achieve a specific outcome, yet struggle when confronted with a different set of tools or different platforms that don’t work the same way. By contrast, a digitally fluent instructor moves confidently and quickly from tool to tool, with an understanding of how and why the technologies may be different. A digitally fluent instructor compares, contrasts, and analyses differences in technologies, understands how those differences might impact their pedagogy, and adjusts accordingly. To me, this ability to adjust is one of the main traits distinguishing the digitally fluent instructor from the digitally literate one.

Finally, the digitally fluent instructor continually focuses on their pedagogical use of the technology. Overarching all their digital skills is the ability to contextualise their use of a specific piece of technology within their own teaching and learning practice. Why are you using it? What are the benefits? What are the drawbacks? Can you anticipate where and how your students may struggle with the technology? How are you hoping this technology will help your students learn? An instructor who asks these kinds of questions is well on the pathway to achieving digital fluency.

A version of this article was previously published here: edtechfactotum.com/digital-fluency-vs-digital-literacy