Issue 108

Term 1 2019

Emily Rodda on treasured stories

Jennifer Rowe, better known by her pen-name Emily Rodda, talks to SCIS about her latest book, His Name Was Walter, and the ability of stories to develop readers — even the most reluctant ones.

Emily Rodda’s life has been a whirlwind of stories. Her family's bond formed not between the pages of books, but between the silences and laughter of their own storytelling. At a young age, Emily taught herself to read by absorbing the words from the books borrowed from her school and municipal libraries, memorising them, then reconstructing them on paper until she was able to read and write independently. Despite a few detours, she ventured on the path to writing that led to the publication of more than 90 books.

We recently had the pleasure of talking to Emily about her life as both a reader and a storyteller, how the two are intertwined, and how we can help young people develop their own love of stories.

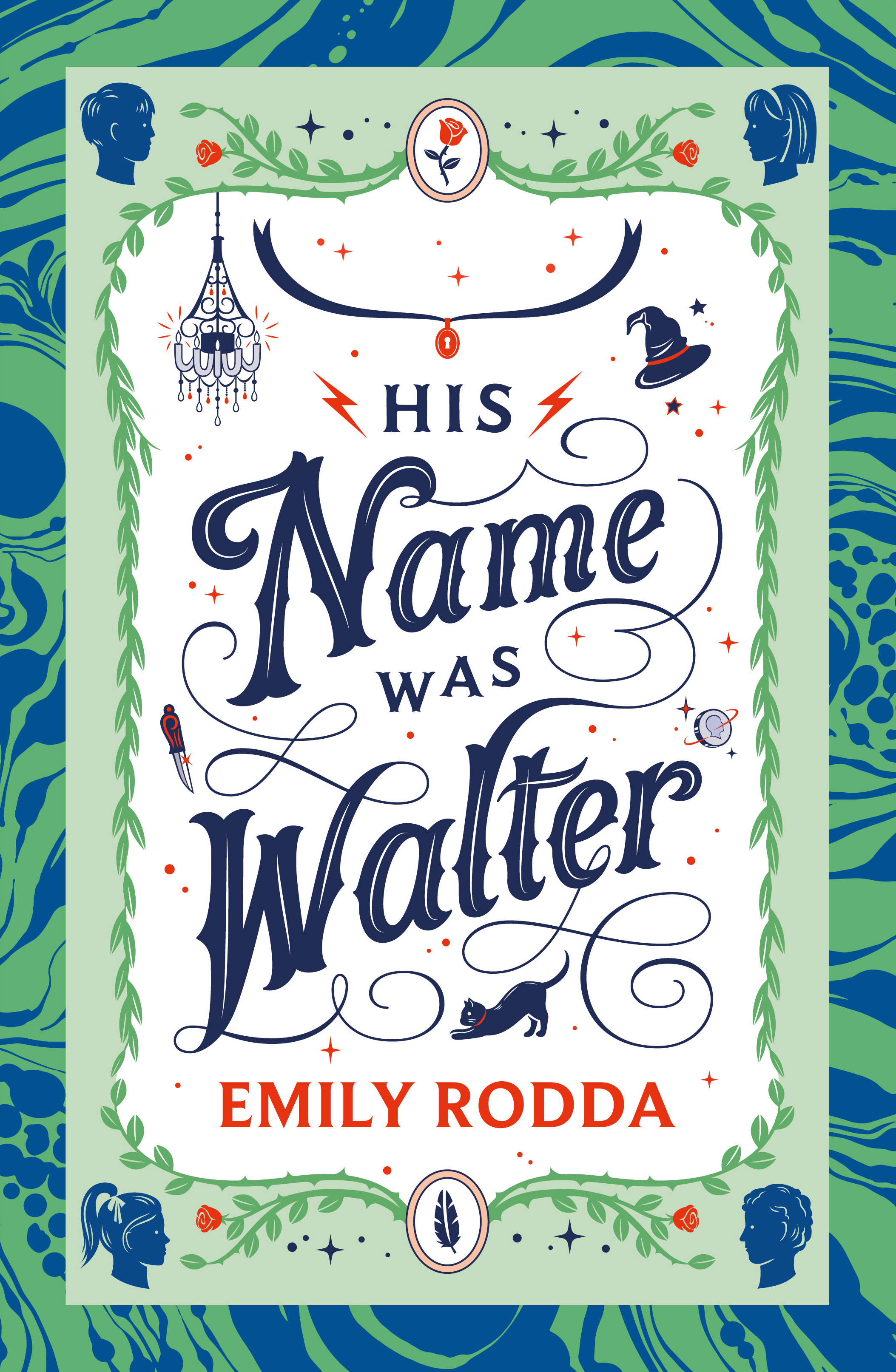

His Name Was Walter

Emily’s most recent book His Name Was Walter explores the power of stories, of shared reading experiences, and of long-ago hidden books as sacred as buried treasure. Weaving together fairytale and historical fiction, entwined with the mysterious and the fantastical, His Name Was Walter tells the story of five people who, after seeking shelter in an abandoned country home, discover a handwritten book that had been eagerly awaiting their arrival. For Emily, writing His Name Was Walter ‘was close to the most wonderful experience of my whole writing life, because it’s a combination of my two great passions: fantasy and real-life mystery.

‘It’s about some kids and their teacher left behind when a school bus breaks down and they have to take shelter. In a secret drawer they find a handwritten book with wonderful illustrations that has been hidden for a long time. They are the first people to look at it, and they begin to read. As they start to get caught up by the story, which reads like a fairytale, they become more and more drawn into the world of Walter, the young hero of the story. Gradually real life and the fable start intertwining and mingling.’

His Name Was Walter by Emily Rodda © HarperCollins 2018

The world of His Name Was Walter was inspired by Emily’s memories of driving through the countryside. ‘Out where there is often a long way between towns, by the side of the road or a little bit inland, you’d sometimes see these deserted houses. They are abandoned and they look sad, and I often used to think, “I wonder what stories those houses have to tell. I wonder who the people were who lived there”. I always wanted to write a story about somebody who had to stay in one of those houses overnight, because I thought that the spirits of the house would have things to say.’

His Name Was Walter explores the magic of reading, with its four main characters all but transported into the world of their newly discovered story. The story is consumed mostly by schoolchildren Colin and Tara, who feel an overwhelming urge to listen to what the book has to say. The two are joined intermittently by their classmates before they, too, become hooked.

The book is, in a way, a shared reading experience between Emily’s readers and her modern-day characters as they delve into this strange and mysterious world together; the characters’ inability to part from the story contagious. ‘Well, that’s what I was hoping,’ she laughs. ‘I was hoping that as my four characters, who are all quite different and have their own problems, become absorbed in the story, so does the reader. That was quite a challenge, actually; it was technically quite difficult, because you get slabs of the fairytale and slabs of real life. That’s why it was such a satisfying experience.’

Finding truth in fairytales

It is no surprise that His Name was Walter was such a gratifying experience for Emily, who had always wanted to write a story within a story.

Emily’s early reading habits were ‘omnivorous’; she would read every fiction book she could lay her hands on. She lists the authors who inspired her early love of reading — Enid Blyton, LM Montgomery, Mary Grant Bruce — careful not to miss anyone lest she offend an old friend. ‘Those writers gave me such enormous pleasure, companionship, friendship. They made me feel how wonderful it would be to be a storyteller.’

From a young age, Emily discovered that she was particularly drawn to fairytales, legends, and fables. ‘I have a relatively wide knowledge of fairytales now, and have always been extremely interested in how they can tell you something about the society in which they were written — and sometimes about things we can very much recognise today.’

Indeed, the fairytale element of His Name Was Walter sprouted from her husband’s experiences. ‘He grew up in an orphanage in England and talks about it quite a bit. I have always found his stories very inspiring, so I dedicated the book to him because he did teach me what it might have been to be Walter.’

Emily continues, ‘I’ve always believed that tales that persist have a grain of truth in them that we should listen to. I find it very compelling, the idea that if something hangs around that long, there is usually a really good reason for it. And it just plucks some string inside us that makes us want to go on with it.’

Developing lifelong readers

Emily feels fortunate that her path to becoming a lifelong reader was straightforward, acknowledging that it isn’t so for many. She has placed a great deal of emphasis on the non-reader throughout her literary career; it is largely what motivates her to continue creating worlds that have the ability to entice even the most reluctant reader.

Emily Rodda (pictured) has lived and breathed stories for as long as she can remember. (Photo: Alex Rowe)

To help develop young readers, Emily recommends trying different methods, without judgement. While Emily’s firstborn daughter was a natural reader, her son was hooked on computer games. Emily bought him a Choose Your Own Adventure book, which he devoured. ‘I gave him another and he consumed that, too, and started asking for them. I kept buying them for him, and just at the point where I thought, “Oh, dear, maybe he will never read anything else,” he started reading everything; he had made the transition.

‘We are all different and different things are right for different people. Some people love humour, some people love romance. Whatever it might be, that’s what you have got to find, and that’s what librarians can do,’ Emily says. ‘If you are not a great reader and you are wandering around shelves trying to decide what to get, it can be very difficult. The beauty of school library staff is that they can see the child, and think, “Ah, I think you might like this”. It’s all about putting the right book into the hands of the person who is going to love it — and having the knowledge to be able to do that.’

School libraries as saviours

‘Stories should be at the absolute centre of any education,’ Emily says. It is for this reason that she has been disheartened to hear of libraries closing, replaced by small bookshelves spread through classrooms. ‘If the library goes, the heart of the school goes, because it’s the place where all the stories of all the world can be.’

‘The thing is,’ Emily continues, ‘libraries often contain computer equipment and everything else, so it can be a whole communication centre — after all, that is exactly what books are. They are quite handy because you can take them to bed, carry them around in your bag, put them in your back pocket. They are a very portable way of communicating. If people read on screens, I do not have a problem with that. What I want them to have are the stories or the information.

‘Of course, libraries are like great big rooms full of doors — doors into other worlds,’ Emily says. ‘You just open the cover and in you go, and you can have anything you want — forever. Because there are thousands and thousands and thousands of doors.’

Advice on becoming a writer

For Emily, reading and writing are largely inseparable. Her natural progression from learning to read was learning to write — first mimicking the words she found in her books, before finding her own voice. ‘I went through a period of copying everyone else’s style and trying to write books like Enid Blyton,’ she recalls. ‘But gradually I learnt my own way.’

For young people who are struggling to develop a story, Emily says: ‘Try instead to create a character that you find interesting, then give that character a world to live in, whether it is fantasy or real, and know how that world sounds and smells; know what things taste like; know what your character’s hobbies are.

‘Write all about that person, and you will probably find that a little story, or a big one, will emerge by itself. Everybody’s life is interesting and your character will have an interesting life, too. Just write and make the character and where they live real to you and to the people you are writing for.’ This process is one that has brought to life the worlds of Deltora and Rin and Rondo. ‘I can honestly say that when I am writing, I am identifying with a character and living in their world. If you’re putting yourself in your character’s shoes, even if that character is quite different from you, you’ll know how that character reacts. It’s when you don’t think hard enough before you start that you can run into trouble.

‘And don’t get discouraged if you don’t win competitions,’ Emily adds. This feeling of discouragement is one that Emily knows all too well. When in her late teens, Emily gave up on her lifelong dream of becoming a writer: ‘I got self-conscious and decided I could never be a great author’. Instead, she pursued a career working in a publishing house before finally submitting her own work for publication. ‘I was in my 30s then, and it was published under the Emily Rodda name — and to my gratification, it won an award. That was an amazing experience.’ Emily encourages young people who are passionate about the craft to continue writing for the love of it, rather than the accolades.

A writer's reward

Reflecting on her time as an author, Emily is grateful that she has had the opportunity to help young people develop into readers. ‘It’s those signing lines of kids all clutching books, sometimes very old and battered, saying things like, “I never used to like reading, but now I do”.

‘Mixing with the children and the parents and hearing stories like that — and seeing their faces so enthusiastic as they ask me about those books — make me wonder: “Who could ask for a more rewarding life?”’

The interview extracts have been lightly edited and reordered where necessary to improve readability or clarity.