Issue 101

Term 2 2017

Navigating the information landscape through collaboration

Elizabeth Hutchinson, Head of Schools’ Library Service in Guernsey, writes that information literacy is at the centre of student learning, making the role of library staff as important as ever.

School libraries and school library professionals have a huge role to play in supporting teaching and learning within a school. I often hear visiting authors comment on being able to identify a good school by how well the library is used. School librarian Caroline Roche penned the phrase ‘heart of the school’, which is used to describe schools whose library is at the centre of learning. But just having a school library does not make students suddenly want to start reading or researching. School libraries need to be looked after and maintained to ensure that good quality resources are available, and the school librarian has to be involved in curriculum discussions and included as part of the teaching and learning team to make an impact. However, even if this is happening, unless teachers fully support and are encouraged to use their school library, their students will struggle to become independent learners.

In a perfect world, all teachers would know how to access their school library and understand why using the library is beneficial to them and their students. Many teachers are resistant: they don’t have the time, they need current information, the books are too old, and there is nothing in the library for them. This is a very blinkered view. I understand that within some subjects, the information changes more quickly than the books can be written — but this is why the school library offers more than just books. Unless we can enlighten and encourage teachers to use these other resources, we are never going to win the battle of our ‘Google everything’ society.

In order for school librarians to remain relevant it is important for us to keep supporting the next new idea in schools. School librarians have always adapted in accordance with changing demands, so the recent idea of innovation and digital literacy in schools is no different. George Couros recently wrote that innovation in schools is a ‘process not a product’; as a librarian, I love this statement because it is the process that we are all about, and it starts with finding and accessing information. To be truly innovative, Couros suggests that we need to consider ‘how we think and what we create, not what we use’. For our students to think deeply, they need to be able to find the information in the first place, evaluate it, decide what to use, and then think about how they can share it. This, in the librarian’s world, is called information literacy.

Information literacy starts in the school library

I regularly hear frustrated teachers talking about the quality of research they receive from their students. One way teachers tackle this is by researching educational websites and then sharing them with their students. Not only is this time consuming, but in a world where we need to create independent learners, it is important that teachers are encouraged to stop spoon-feeding their students – not by leaving them to type the question into Google, but with something far better. The school library can lead students directly to good quality resources, both physical and online, but it is often forgotten and goes unused. Yet the library is by far the best place to start creating independent learners within a school.

As more schools embed digital literacy and want innovative teaching within their curriculum, trained school library staff become even more important. The school library not only enables students to learn how to search a database and find quality resources via the online catalogue, but it also provides access to other online resources. These, like all academic resources, require real skills to navigate. You can’t type the question into any academic database, you have to think of keywords and understand research techniques. The school librarian can teach students the best way to find and access information from these sources, and can ensure that these skills are embedded throughout the curriculum. If teachers and school librarians work together to ensure students use these resources, the students’ skill set and quality of work will vastly improve.

As the conversation about digital literacy and independent learning changes, we have the perfect opportunity for school librarians to turn the tide and demonstrate to teachers why our students should use the school library. Knowing how to find and use school library resources should certainly be considered a ‘digital skill’ — one that needs to be taught to our students.

Students are not necessarily going to use the school library without teacher encouragement. Collaboration between the teacher and the school librarian is known to have an impact on student attainment, and part of this is about ensuring they use the right resources. Many do work together, but what happens if a teacher is not aware of how beneficial the school library is? Our students need to understand how it works, and the conduit to this is the teaching staff.

Schools are expected to use technology in their classrooms to demonstrate innovative teaching. Imagine a class where the teacher was collaborating with the librarian, and students were using the online catalogue to find books and websites for research: this would be classed an innovative lesson. The school library provides the opportunity to find good quality information, but teachers need to guide students there — and for this to happen, teachers need to know and understand themselves why quality library resources are important.

Identifying resource quality through referencing

Some teachers believe that Google is the quickest way to find information, and therefore do not discourage students from researching in this way, which is where our problems lie. When teachers understand the importance of referencing and are aware that libraries provide educational resources, at the right level for students in the school, they can encourage students to use them. I am not saying that students should never use Google, but we need to have a way of evaluating where they are getting their information. This can be done through referencing. Teachers should educate students about plagiarism and copyright, and expect students to reference their research. The reality is that if teachers do not check where the information is coming from, the students are never going to see the need to provide quality work.

How can library staff help?

Students need to be aware of the consequences of poor research, and this is where we can support and provide training. School librarians have just been handed the perfect opportunity to work alongside teachers using our skills to link with their curriculum needs. We are trained to teach digital literacy skills and use innovative ideas, and we now have the opportunity to share these skills. Our problem is that, just like the lack of understanding by some teachers of what information literacy is and how the school library supports this area, we now have the same problem with digital literacy. Conversations with head teachers become really important.

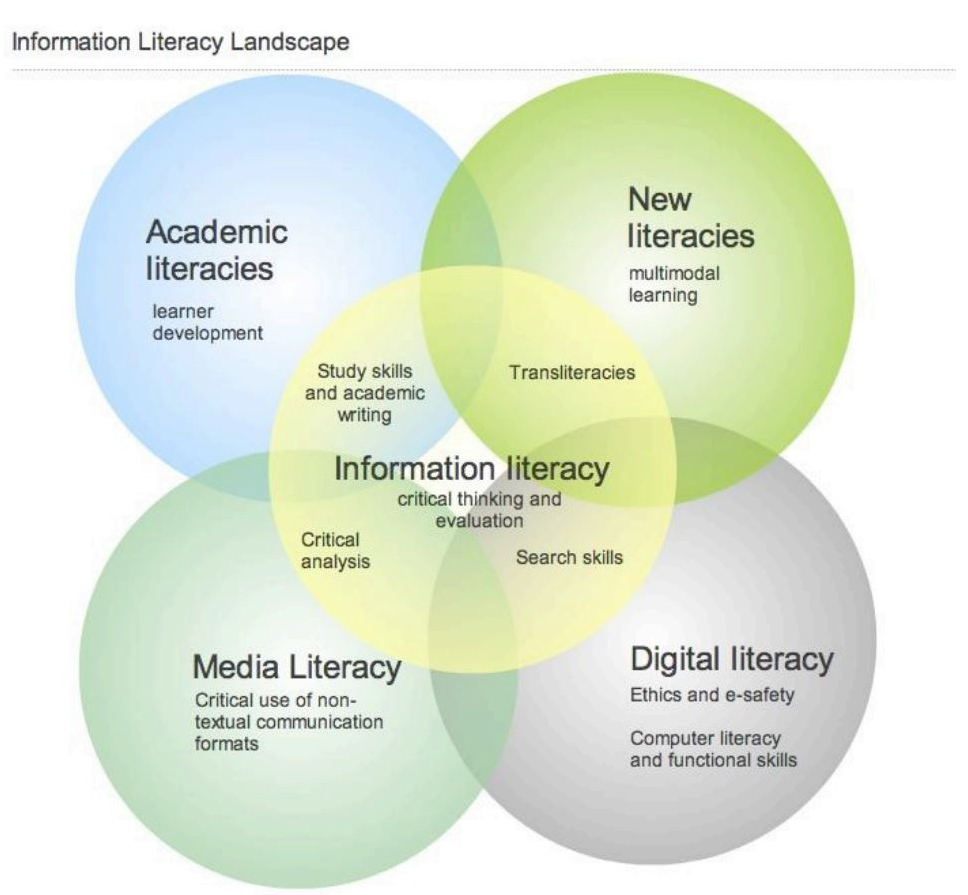

The wonderful diagram of the information literacy landscape (see above), which demonstrates how all literacies fit together, can definitely help start the conversation about what information literacy is and how it should be at the heart of learning.

School librarians need to be aware of current research, the importance of their professionalism, and the power of their own advocacy. It is essential to talk to senior leaders, discussing with them the importance of embedding information literacy into the curriculum and providing evidence that librarians can make a difference. Attending teacher meetings and curriculum-planning sessions, keeping the conversation going about the resources in the library, and talking about how you can support teachers and students in the classroom are all necessary. It is important to provide training and to demonstrate best practice whenever you can because it can have a huge impact. Through talking and sharing, we will not only ensure students get skills for the future, but also guarantee our teachers understand how we can support them in their journey with digital literacy and innovation.

References

- Couros, G 2017, The principal of change, accessed 1 February 2017, http://georgecouros.ca/blog/archives/6999

Image credits:

- Secker, J & Coogan, E 2011, A new curriculum for information literacy: executive summary, accessed 5 February 2016, http://ccfil.pbworks.com/f/Executive_summary.pdf. CC BY-NC-SA 3.0.